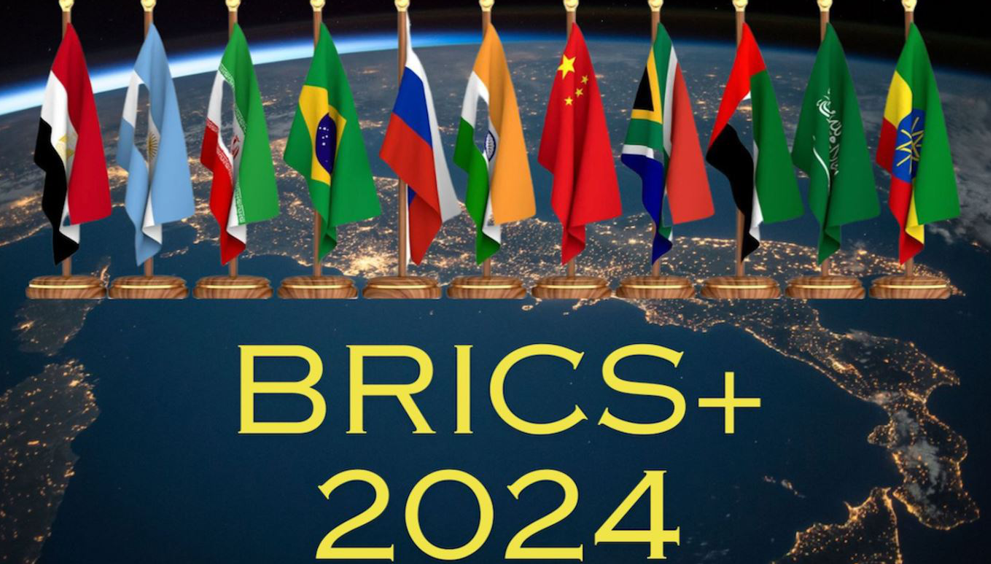

Reshaping Global Governance: the Global South, BRICS and the West

BRICS’ resilience should be understood in the context of the shifting international order, with geopolitical fragmentation providing the Global South with greater flexibility to pursue its strategic goals. For the West, engaging on the Global South’s most pressing concerns may help to foster more constructive partnerships. Established in 2009, its informal structure, diverse membership – often divided by long-standing geopolitical rivalries – and varied agendas defy easy categorisation within traditional schemes of free trade, economic integration or political cooperation. These factors have prompted scepticism about the organisation’s significance as a multinational forum and its long-term viability. Yet BRICS has continued to expand and prosper, building institutions like the New Development Bank and welcoming new members, reflecting its strong appeal to the Global South, as evidenced by the numerous countries eager to join.

Global governance architecture not fit for purpose

BRICS’ resilience despite the odds must be understood in the context of current geopolitical shifts. The international order is undergoing a transformation and rebalancing, driven by the rising economic influence and diplomatic assertiveness of China and several emerging powers in the Global South. As the world moves towards multipolarity, more countries are aligning with China (at least economically), often at the expense of the United States and the West. Meanwhile, a revanchist Russia has emerged as another focal point attracting many states, particularly those from the Global South. In this fragmented global landscape, the governance system established after the Second World War, which is centred around the US (and the US dollar), faces increasing criticism from Global South powers, who consider it outdated and unrepresentative of current economic and geopolitical realities. The degree of change and disruption these powers seek varies, with some pushing for outright revisionist agendas, while others advocate for reform within the current system. Simultaneously, Global South powers are becoming more assertive in shaping their strategic agendas and are increasingly willing to diverge from Western approaches when deemed necessary. Their growing confidence intensifies competition between Western powers, Russia and China to win the Global South’s support. In turn, this trend may grant the most skilled actors in the Global South greater flexibility and room to manoeuvre in pursuing their policy priorities.

The BRICS experiment has both arisen from and encapsulates these dynamics: its founding members include China and Russia; its main unifying feature is a shared commitment to reforming the global system, notably its financial architecture; and it brings together a varied group of actors from the Global South with diverse geopolitical inclinations and foreign-policy objectives. Its loose structure reflects not only the economic, political and geopolitical diversity of its members but also a desire to keep options open for countries active in other forums, such as the G20 and the India–Brazil–South Africa Dialogue Forum (IBSA). At the same time, the group’s rising economic clout, combined with China’s presence – a vital economic partner for most developing states – means that BRICS membership is an attractive prospect for Global South countries.

The limitations of a Western-centric lens

If China and Russia’s presence within BRICS had already raised concern in many Western capitals about the group’s alleged anti-Western bias, the admission of Iran (alongside Egypt, Ethiopia and the United Arab Emirates) in January 2024 heightened these anxieties. While it is reasonable to assume Russia, Iran and China share a degree of animosity vis-à-vis the West and the US-centred geopolitical order, there are broader dynamics at play that must be considered in any strategic assessment of BRICS and Global South politics. Geopolitical fragmentation is providing the Global South with greater room to manoeuvre in pursuing its own strategic goals. Most Global South countries do not necessarily see themselves as anti-West but rather as non-West. They have distinct domestic and foreign-policy agendas and are increasingly adept at navigating geopolitical competition, engaging with powers like China and the US based on their own interests. Latin America exemplifies this, situated in the United States’ traditional sphere of influence yet counting China as its largest trading and financial partner. BRICS is no exception to this trend, with Brazil, India and South Africa holding the flag for this ‘non-alignment movement 2.0’ and advocating for reforms within the current order while working to moderate the group’s more anti-Western positions. These countries may be seen as junior partners within BRICS, but they have great-power potential and ambitions and promote an agenda that resonates with many developing states. Their ongoing involvement in BRICS enhances the group’s appeal to the wider Global South, giving them leverage in balancing.

Finding common ground

Western states would benefit from acknowledging that – just like their own – Global South countries’ decisions can be shaped by realpolitik considerations. They might find therefore that engaging with these countries on their most pressing concerns and legitimate demands is an effective way to foster more constructive partnerships. While challenging China’s economic influence in most Global South states may be a tall order for a financially stretched West, finding common ground on reforms to the global governance system and advancing towards a more inclusive international financial architecture are both reasonable and desirable objectives. The Pact for the Future, adopted at the UN General Assembly in September 2024, marks a significant step towards reforming global governance to better reflect the current geopolitical landscape. Similarly, the landmark agreement at COP28 in 2023, which established a loss and damage fund to help developing countries with climate adaptation, addresses a long-standing demand and contributes to a more climate-just financial architecture. In fact, mobilising sufficient climate funding to support mitigation efforts in the Global South – including fostering alternative economic models in strategic areas like the Amazon in Latin America – could be an effective starting point, given the reciprocal benefits this could yield for both developed and developing states. Furthermore, the West could strengthen its appeal as a partner for developing countries rich in critical minerals by promoting sustainable practices, fostering local job creation and transferring know-how and technologies. This approach would not only address environmental concerns but also support economic development, making these partnerships more mutually beneficial and attractive to resource-rich developing countries. For the West, being pragmatic and focusing on areas of common interest may prove the best engagement strategy with the Global South, and ultimately lead to a more balanced and resilient international system.

By Irene Mia

Source: www.iiss.org

English

English