Latin American Prospects for BRICS

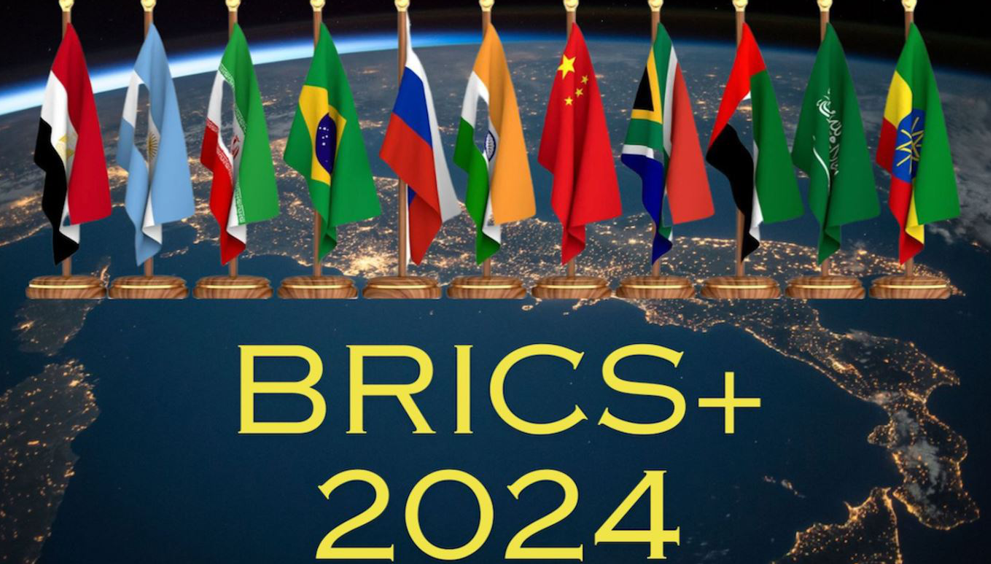

The BRICS Summit held in Kazan from October 22–24, 2024, brought attention to several defining factors regarding Latin American countries that will be important for the continent’s political and economic development in the near term. With the admission of two countries from this region as associate members of the bloc, the Latin American presence in the pool of developing countries seeking to increase their weight in shaping the new world order is set to grow. Bolivia and Cuba joined BRICS as partners along with 11 other countries: Algeria, Belarus, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Malaysia, Nigeria, Thailand, Turkey, Uganda, Uzbekistan and Vietnam. Together with the core BRICS countries and the new members who joined a year earlier, this means a fundamentally new format of international interaction, where the diversity of participants creates a platform for polyphonic dialogue. While their overarching interests align, each country has its own priorities and expectations from BRICS membership.

Bolivia’s interests

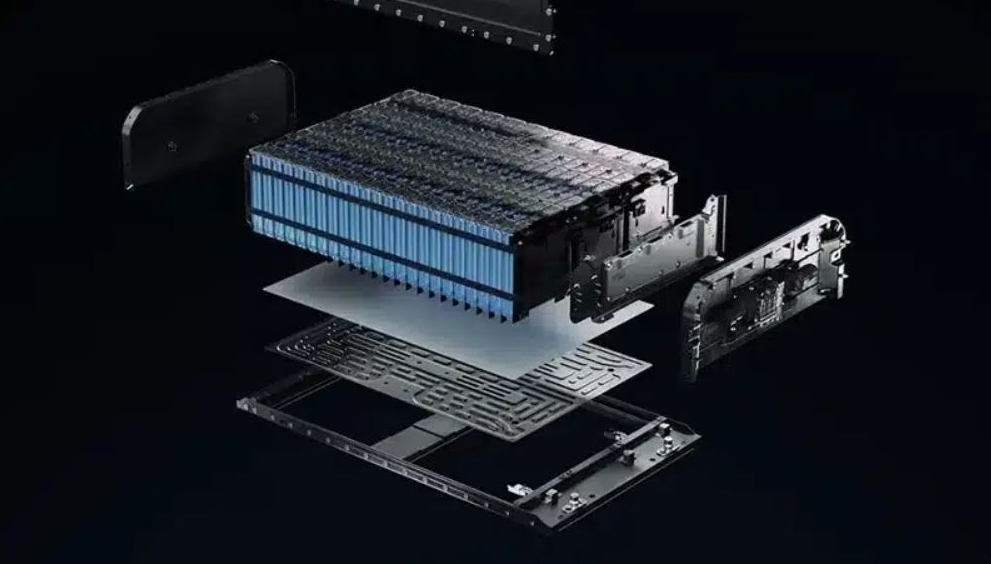

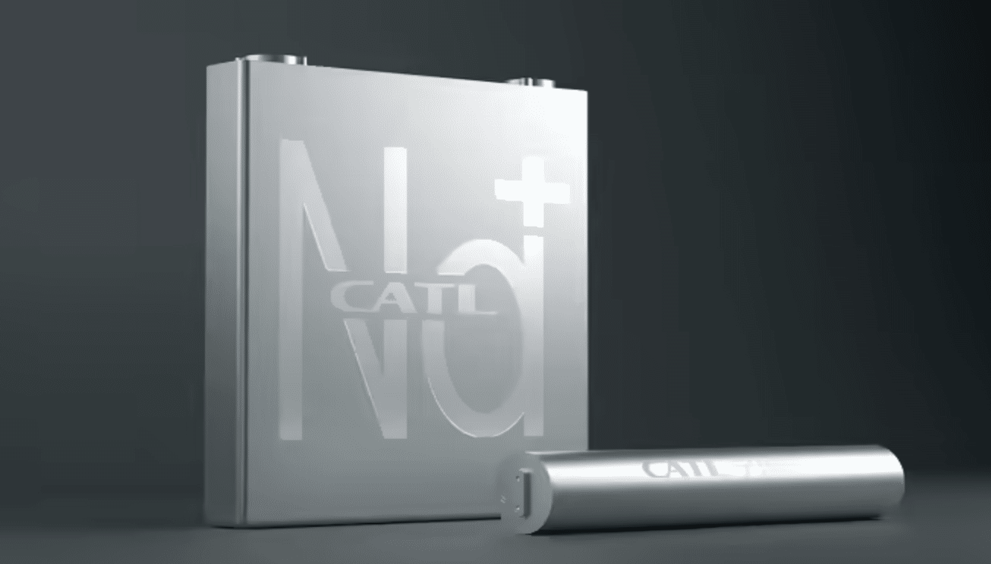

The Plurinational State of Bolivia is developing a left-leaning economic model that prioritizes the social redistribution of state revenues, mainly generated from the exploitation of the nation’s natural resources. Bolivia is rich in hydrocarbons, primarily natural gas, and holds the world’s largest lithium deposits, estimated at over 21 million tonnes. While the export of Bolivian hydrocarbons (mainly to neighboring Brazil and Argentina) remains a traditional revenue stream, the lithium industry is a relatively recent addition to the country’s foreign economic priorities. Lithium nationalization in 2008 gave a start to the development of Bolivia’s deposits, but for several reasons—which include difficulties in attracting investment, a lack of technological infrastructure, opposition from indigenous communities and local environmental organizations—full-scale exploitation of deposits has never been launched, aside from a few pilot projects. It was only in 2021 that two Chinese companies and Russia’s Uranium One Group, part of the management circuit of Rosatom state corporation, won the development tender.

By joining BRICS as a partner, La Paz aims to cement its position as a supplier of raw lithium to the global market. Given the vast scale of its national reserves, the Bolivian government is keen to expand its pool of international investors. In turn, La Paz is ready to offer its partners cooperation in other areas, such as energy resources and food production. BRICS countries already dominate Bolivia’s foreign economic relations, led by Brazil ($3.5 billion), China ($3.5 billion) and India (around $2 billion), which is a major importer of Bolivian gold. Beyond trade, China is also an active investor in Bolivian infrastructure and technology projects.

Cooperation with Russia is growing more important for Bolivia. The lithium agreement is part of a broader strategy between the two governments to encourage investment in key sectors. On the sidelines of the Kazan Summit, Presidents Luis Alberto Arce and Vladimir Putin held a bilateral meeting to discuss joint nuclear technologies (Bolivia has opened a unique high-altitude El Alto Nuclear Research and Technology Center (CNRT), designed for peaceful nuclear applications and built by Russian experts), cooperation in education, lithium contracts and other issues that bring the interests of the two nations closer together. La Paz and Moscow also share a vision for building a global world order and advocate a multipolar world.

At the same time, the complex political situation in Bolivia and the conditions in which the country may find itself by the 2025 general elections cannot be ignored. The dispute over the presidential candidacy threatens to undo the political project that has been unfolding in the country since 2006. Social divisions and an economic crisis are fueling deep uncertainty and pessimism in Bolivian society about the country’s development outlook. BRICS could be a new opportunity for economic breakthroughs if the current course is maintained after the elections. However, if opposition forces come to power, Bolivia may well follow the path of Argentina, which abandoned plans to join the bloc after a change of government.

Cuba’s expectations

For Cuba, international support from BRICS countries means a chance to overcome its long-standing and multifaceted crisis, which the island cannot tackle on its own. Havana views its primary objectives as countering US unilateral restrictive measures and seeking alternative sources of financing. While Cuba maintains trade relations with all BRICS nations, their share in the total trade turnover is modest. China is the top trading partner among BRICS members, accounting for about 13% of Cuba’s foreign trade. Trade between the two nations saw its biggest growth between 2005 and 2015, but in recent years there has been a decline in Cuban–Chinese interaction. Although Cuba joined China’s Belt and Road Initiative in 2018, meaningful results have yet to materialize. Latin American countries account for one-third of Cuban foreign trade, with Brazil’s share at just 3.2%. The expansion of trade and economic relations with Russia has pushed its share in Cuba’s trade to 7%. Strengthening foreign economic relations is, therefore, a top priority for Cuba.

Meanwhile, the main obstacle to this goal is the economic embargo imposed by the United States, with Cuba consistently calling on the international community to demand its lifting. Although bilateral relations thawed during the administration of Barack Obama, and both sides attempted to find common ground on some fundamental issues, neither is ready to abandon its stance. Nor does Havana’s rapprochement with BRICS signal a complete departure from attempts to engage with Washington constructively. The US will still be in the focus for Cuba. However, given the new balance in the White House following recent elections, it will not be easy for Havana to maintain the status quo and prevent the hegemon from increasing its pressure.

Contradictions between Venezuela and Brazil

One country that shares Cuba’s aspirations is Venezuela, which faces severe Western sanctions and a serious economic crisis. Caracas primarily counts on the assistance of Russia and China, but Venezuela’s relations with other members of the bloc are much more complex. For instance, this is true for Venezuela’s ties with India, which revolve around India’s demand for oil from this Bolivarian country. Due to US sanctions, India stopped oil imports from Caracas in 2019 but is ready to resume cooperation after the restrictions are eased. That said, New Delhi does not provide any political support to the Venezuelan government, and the prospects for broadening ties in other areas are slim.

Brazil’s veto on Venezuela’s inclusion in the group of BRICS partners has exposed deep divisions within the region and intensified the rift within Latin America’s left-wing political landscape. The fact that it was the position of Brazil, the region’s only representative in BRICS, that became an obstacle for Venezuela, sparked the most backlash and bitter antagonism from Caracas. For Nicolas Maduro and his team, potential BRICS membership appears to be an important foreign policy objective. With close ties to Russia and good relations with some Asian and African nations, Venezuela seemed well-positioned for admission. In addition, the country has robust relations with several BRICS members, including Iran and China. In 2023, Caracas signed an all-weather strategic partnership agreement with Beijing (China has similar agreements only with Russia, Belarus and Pakistan). Until recently, there had been no overt opposition to Venezuela’s membership in the group.

Meanwhile, Venezuela and Brazil have experienced diplomatic ruptures in the recent past. In 2019, relations were severed after then-Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro recognized opposition leader Juan Guaido as Venezuela’s interim president. Diplomatic ties were only restored in 2023 when Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva returned to power in Brazil. However, relations between the two nations soured again after the presidential elections in the Bolivarian country in July 2024, when Maduro was declared the winner. The results remain unrecognized by several countries, including Brazil, which has officially called for the release of electoral records and withheld recognition of the current Venezuelan government. This rift has exacerbated the row over Brazil’s veto, leading Maduro to recall his ambassador for consultations and make harsh remarks against Brazil.

Compounding matters, Brazil is set to chair BRICS in 2025, which makes it unlikely for Venezuela to join the bloc before it mends ties with Brasilia. Given Brazil’s consistency and firmness in pursuing its foreign policy, the matter may have to be put on ice indefinitely.

Brazil’s aspirations

As of now, Brazil remains the only Latin American country represented in BRICS as a full member. It plays one of the main roles in promoting the agenda of the Global South on the global stage. Central to this effort is Lula da Silva, who, during his two previous presidential terms (2003–2006, 2007–2011), pursued an active policy of strengthening ties with developing nations in Asia and Africa. His commitment to multilateralism in foreign policy reflects the national tradition of positioning the country as a regional power with global ambitions.

The rotation of the BRICS presidency, coupled with the extension of Dilma Rousseff’s tenure as head of the New Development Bank, is likely to favor Brazil’s ability to expand its role in the group and the world. In a challenging domestic political climate, where the government faces strong opposition from a large part of society, success in the international arena will be crucial for Lula da Silva. While the South American giant is now struggling to consolidate Latin American neighbors around it and drive regional integration, current Brazilian diplomacy has focused its efforts on global initiatives. International engagement is part of Brazilian national identity. Its historical tradition of assuming the role of a regional leader in multilateral forums and accumulated experience that Brasilia leverages as a diplomatic asset enable it to act in the international arena from a position far surpassing that of a developing nation burdened by major internal socio-economic problems and lacking the military capabilities of the great powers. Brazil’s vision of a world based on international rules, where every nation has a say, is what it seeks to promote in the global context, harnessing the potential of BRICS.

External factors

Other Latin American nations have also signaled their willingness to join the bloc. These include Honduras, Nicaragua (which submitted applications ahead of the Kazan Summit in 2024) and Colombia, highlighting broad interest and intention to deepen cooperation within the Global South paradigm. Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that Argentina’s accession to BRICS, which was denounced by President Javier Milei, may remain on the agenda and be postponed for a while. Since Argentina has already been invited and its political landscape is fluid, the prospect of joining the bloc could become a reality for this country if BRICS-aligned forces regain power in Buenos Aires.

Finally, an important factor in expanding the participation of Latin American countries in BRICS will be US policy toward the region under Donald Trump. While his cabinet has not yet been approved and no clear directions have been outlined, various speculations heighten uncertainty and heat up expectations of different forces but fail to provide an objective picture. However, it is clear that Latin American countries once again find themselves in a position where they must react to the steps taken by the northern hegemon. The efforts to establish an independent course, made over the past decades by various governments in the region—mostly left-leaning—have not yet yielded the desired results and have not become a tangible reality. Therefore, their foreign policy, including in other areas, will depend to a certain extent on the Washington factor. In this sense, BRICS, not only for the newly joined Cuba and Bolivia, could become a platform to help Latin American countries reduce their dependence on the US and build alternative routes for their foreign economic and foreign policy activities.

Amid the global uncertainty that plagues today’s world, Latin American countries are looking for appropriate mechanisms to advance and strengthen their positions. Key among them are coalition-based forms of international cooperation, such as those offered by BRICS, a partnership that promises mutual benefits.

Tatiana Vorotnikova – PhD in Political Science, Academic Secretary at the Institute of Latin American Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences.

RIAC

Source: russiancouncil.ru

- brics1

English

English