BRICS post-Kazan: A Laboratory of the Future

The Russian presidency of BRICS 2024 could not have chosen a more multicultural and multi-nodal site to host a summit laden with enormous expectations by the Global Majority. The southwestern Russian city of Kazan, on the banks of the Volga and Kazanka rivers, is the capital of the semi-autonomous Republic of Tatarstan, renowned for its vibrant mix of Tatar and Russian cultures.

Even though the BRICS summit took place in the Kazan Expo – a sort of multi-level station connected to the airport and the aero-express link to the city – it was the Kazan Kremlin, a centuries-old fortified citadel and World Heritage Site, that imposed itself as the global image of BRICS 2024.

That spelled out, graphically, a continuity from the 10th century onwards through Bulgar culture, the Golden Horde, and the 15th–16th-century Khanate all the way to modern Tatarstan.

The Kazan Kremlin is the last Tatar fortress in Russia with remnants of its original town planning. The global Muslim Ummah did not fail to observe that this is the northwestern limit of the spread of Islam in Russia. The minarets of the Kul Sharif mosque in the Kremlin, in fact, acquired an iconic dimension – symbolizing a collective, trans-cultural, civilization-state effort to build a more equitable and just world.

It has been an extraordinary experience to follow throughout the year how Russian diplomacy managed to successfully bring together delegations from 36 nations – 22 of them represented by heads of state – plus six international organizations, including the United Nations, for the summit in Kazan.

These delegations came from nations representing nearly half of the global GDP. The implication is that a tsunami of thousands of sanctions imposed since 2022, plus relentless yelling about Russia’s “isolation,” simply disappeared in the vortex of irrelevance. That contributed to the immense irritation displayed by the collective west over this remarkable gathering. Key subtext: there was not a single official presence of the Five Eyes set-up in Kazan.

The various devils, of course, remain in the various details: how BRICS – and the BRICS Outreach mechanism, housing 13 new partners – will move from the extremely polite and quite detailed Kazan Declaration – with more than 130 operational paragraphs – and several other white papers to implement a Global Majority-oriented platform ranging from collective security to widespread connectivity, non-weaponized trade settlements, and geopolitical primacy. It will be a long, winding, and thorny road.

Onward drive, from Asia to the Muslim world

The BRICS Outreach session was one of the astonishing highlights of Kazan: a big round table re-enacting the post-colonial Bandung 1955 landmark on steroids, with Russian President Vladimir Putin opening the proceedings and then handing the floor to representatives of the other 35 nations, Palestine included.

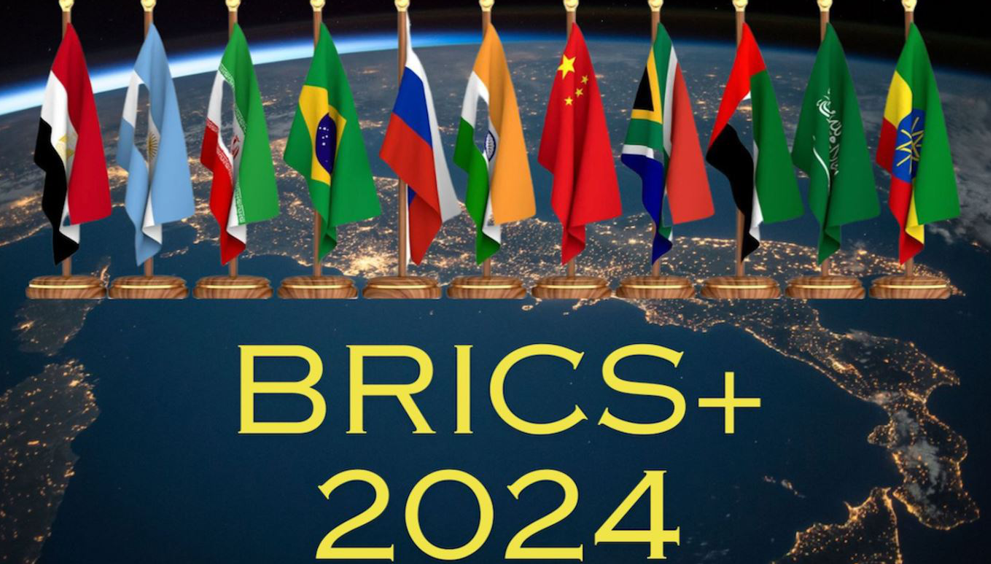

The first round of BRICS expansion last year focused heavily on West Asia and Northeast Africa (Iran, UAE, Egypt, and Ethiopia, with Saudi Arabia still deciding its final status). Now, the new “partner” category – 13 members – includes, among others, four Southeast Asian powerhouses, including Malaysia and Indonesia, the top two powers in the Heartland, Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan, and NATO member Turkiye.

Muslim-majority nations are all over the place as part of the BRICS drive; in parallel, Asia as a whole is fast becoming prime BRICS territory.

In-depth debate on how to develop a new global financial and payment system practically from scratch – a key plank of de-westernization – has been relentless across the BRICS matrix since February. By early October, the Russian Finance Ministry announced the launch of BRICS Bridge – inspired by Project mBridge: a digital payment platform for cross-border trade in national currencies.

Western hegemons are already scared. The Swiss-based Bank of International Settlements (BIS) is now mulling to shut down mBridge – backed, among others, by commercial banks from BRICS members China and UAE, BRICS partner Thailand, quasi-BRICS member Saudi Arabia, and the Hong Kong Monetary Authority.

The excuse is “geopolitical risks” – a euphemism for mBridge making it harder to enforce unilateral, illegal US and EU sanctions. That ties up, for instance, with global banking giant HSBC officially joining China’s interbank cross-border payment system (CHIPS), which is similar to the Russian SPFS. From CHIPS/SPFS to BRICS Bridge is just a short step.

The key issue – a serious worry for the Global Majority – is how to settle trade surpluses and deficits. When it comes to initiatives such as BRICS Bridge and BRICS Pay – the test run of the BRICS Pay card took place a week before Kazan – that’s not a technical issue.

What matters is not so much how to send a currency but what to do with that currency at the other end. It’s an eminently political affair, but there are ways around it, as the predominant, western-controlled SWIFT system is very primitive.

The BRICS working groups also paid close attention to facilitating investment; these are open systems, good for BRICS members and partners. Once companies from whatever latitude start joining, critical mass for growth/investment will be just a shot away.

All of the above embodies the spirit of BRICS starting to function in 2024 – driven by the Russian presidency – as a global laboratory, testing every possible model, old and new, to be applied in a multi-nodal way. Diplomatically, the Kazan Declaration stated that new approaches should be presented to the UN and the G20; yet, realistically, there’s no evidence the collective western bloc will receive them with open arms.

The de-dollarization nitty-gritty

Apart from establishing the 13 new partners – constituting a large, transcontinental, de facto BRICS zone – Kazan advanced two key platforms: BRICS Clear and the BRICS (Re)Insurance Company.

BRICS Clear is a multilateral settlement/clearing system for both BRICS trade and trade between BRICS and their partners (as it stands, applying to 22 nations). The key aim, once again, is to bypass SWIFT.

BRICS Clear will use national currencies for international trade. Everything will be transacted via a stablecoin – a unit of account – managed by the NDB, the Shanghai-based BRICS bank.

As top French economist Jacques Sapir has pointed out, “trade requires insurance services (for both the contract itself and transportation); these insurance services involve reinsurance activities. With the BRICS (Re)Insurance Company, BRICS is building its independence from western insurance companies.”

BRICS Clear and BRICS (Re)Insurance, in the short to middle term, will have enormous consequences for global trade and the use of US dollars and euros. Trade flows, intra-BRICS and between BRICS partners – already at least 40 percent of the global total – may rise exponentially. In parallel, western-controlled insurance and reinsurance companies will lose business.

That’s de-dollarization in practice – arguably the BRICS Holy Grail. Of course, India and Brazil never refer to de-dollarization in the manner of Russia, China, and Iran, but they do support BRICS Clear.

Sapir predicts that up to 2030, the BRICS Clear effect may result in the dollar share in Central Bank’s reserves falling “from 58 percent to around 35-40 percent.” Significantly, that would imply “massive sales of Treasury bonds, causing a collapse of the public bond market and significant difficulties for the US Treasury in refinancing United States debt.” The Hegemon will not take that lightly, to say the least.

Lab experiments counter-acting arrogance

These BRICS geoeconomic breakthroughs – call it lab experiments – mirror diplomatic coups such as India and China, mediated by Russia, announcing on the eve of Kazan their drive to settle bilateral troubles in the Himalayas to advance the unifying, pan-cooperation BRICS agenda.

Solving geopolitical issues among member-nations is a key BRICS priority. The China–India example should translate to Iran–Saudi Arabia when it comes to their involvement in Yemen and Egypt–Ethiopia when it comes to the controversial building of a major dam in the Nile. BRICS sherpas openly admit that BRICS needs an internal institutional mechanism to solve serious problems among member-states – and, eventually, partners.

And that brings us to the ultimate incandescent tragedy: Israel’s military offensives in Gaza, Palestine, Lebanon, Yemen, Syria, and Iran.

BRICS sherpas revealed that two scenarios were being actively discussed in the closed sessions, as well as the bilateral meetings. The first foresees an Iran–Israel Hot War, with Lebanon turned into a major battleground, leading to a “chain reaction” involving several Arab actors.

The second scenario foresees a pan-West Asia crisis, involving not only neighboring nations but what would coalesce into coalitions – one pro-Arab, the other pro-Israeli. One wonders where dodgy actors such as Egypt and Jordan would fit in. It’s unclear how BRICS, as a multilateral organization, would react to both scenarios.

Dreadful realpolitik did not stop in its tracks to watch the BRICS high-speed train leave the Kazan station. Israel staged its puny strike on Iran immediately afterward, and the collective west pronounced the elections in Georgia null and void because they did not like the result – even though the OSCE issued a rational report about it.

The collective west’s incomprehension of what transpired in three historic days in Kazan only highlighted their astonishing arrogance, stupidity, and brutality. That’s precisely the reason why the BRICS matrix is working so hard to come up with the lineaments of a new, fair international order, and despite an array of challenges, will continue to flourish.

Pepe Escobar is a columnist at The Cradle, editor-at-large at Asia Times and an independent geopolitical analyst focused on Eurasia. Since the mid-1980s he has lived and worked as a foreign correspondent in London, Paris, Milan, Los Angeles, Singapore and Bangkok. He is the author of countless books; his latest one is Raging Twenties.

English

English