Business Model Innovation: Shifting the Focus to Small Economies

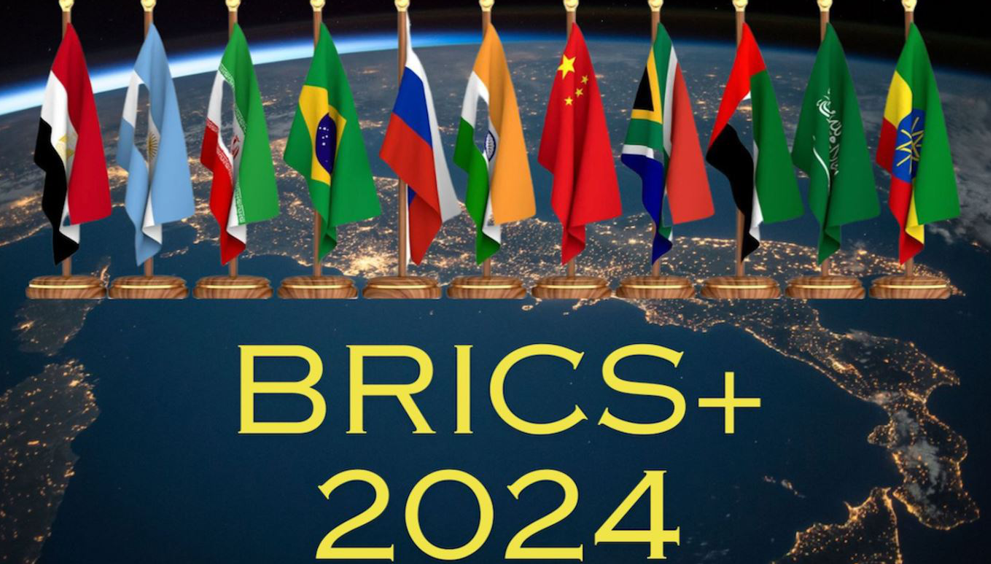

Several months ago we postulated a BRICS+ business model for companies that explored the scope for exploiting the BRICS diverse presence in the main regions of the developing world. But while this business model had its clear advantages, it also contained some drawbacks, most notably pertaining to the degree to which BRICS/BRICS+ economies could be/were integrated into regional/global supply chains in the midst of mounting geopolitical risks. Another problem that we noted was the lack of intra-BRICS trade liberalization and the still relatively high trade barriers across BRICS+. The question then is: what kind of business model would enable companies to leverage the high number of trade accords concluded by some of the most open economies on the international arena? What we then propose is a business model that is in some respects the reverse of the BRICS+ paradigm, namely, it is based on a different array of economies, with the quality of economic policies and economic openness being the key criteria for the formation of such a business-oriented platform.

The markets that are endowed with the widest networks of trade alliances in the world economy are largely represented by small open economies that have a strong track-record of high-quality economic policies. Collectively, these countries could be brought under the umbrella of the acronym OASES – Oriental Republic of Uruguay (ORU) in South America; Austria and Switzerland in Europe, United Arab Emirates (Emirates) in the MENA region; and Singapore in East Asia. These are some of the smallest countries in their respective regions that at the same time have substantial economic clout, have relatively high standards of living and have developed a diverse network of trade alliances.

In terms of economic openness Uruguay’s import tariff (simple average MFN applied) of 10% is among the lowest in Mercosur – broadly on par with Paraguay’s 9.6%, and lower than in Argentina (13.3%), Brazil (11.1%) and Bolivia (11.7%). Singapore stands out not only in the ASEAN region, but also global with its simple average import tariff level of 0% – this compares with 8% in Indonesia and 9.6% in Vietnam. Austria’s import tariffs are unified at the common EU level of 5.1% and are close to the levels observed in Switzerland (5.6%). Import tariffs in UAE at 4.7% are on par with Kuwait and Qatar, slightly higher than in Bahrain (4.5%) and notably lower than in Saudi Arabia (6,3%) and Oman 5.6%).

From a business strategy standpoint, it is not even so much the level of import tariffs per se, but rather than network of free trade alliances that the economy has developed that make it an attractive element of the company’s business model. In this respect, Switzerland stands out as a key focal node for OASES – it has trade agreements or is negotiating trade accords with all other parts of such a platform – all in all Switzerland has 35 free trade agreements (FTAs) with 45 countries or blocs]. Another key node in terms of trade linkages is Singapore – it has a total of 27 implemented FTA agreements], with a leading role in the global economy in the sphere of forging digital economic agreements (DEAs). In the case of UAE, under the Greater Arab Free Trade Area Agreement, the UAE has free trade access to Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, Jordan, Egypt, Iraq, Lebanon, Morocco, Tunisia, Palestine, Syria, Libya, and Yemen. In South America, while Uruguay may be behind Chile in the number of trade accords, it has the benefit of the Mercosur platform of regional integration and has launched FTA talks with China in addition to the existing accords with Mexico and Chile.

Apart from the extensive network of trade accords, OASES economies are key members of regional integration arrangements – Switzerland in EFTA, Austria in the EU, Uruguay in Mercosur, UAE in GCC, Singapore in ASEAN – that through free trade provide possibilities for companies to expand shipments and production to the regional partners of OASES economies. The combination of regional and extra-regional accords provides corporates that are localized in OASES economies with greater optionality and lowers the costs of distributing goods and services to other parts of the global economy. Across consumer categories, the OASES business model may target the middle to high-end parts of the income spectrum that have a particular predilection to established brands. The OASES business model may hence be further reinforced and enriched by such business models/strategies as ultimate luxury, open business model, and ingredient branding.

Across sectors, given the competitive advantages of OASES in the services sector, these small open economies may be used as platforms for companies in launching new services that could then be scaled up to other parts of the respective regions of the global economy. There may be also competitive advantages of the OASES business strategy in manufacturing. As we have already pointed out above, one of the weaknesses of the BRICS+ business model is the risk to the integration of some of the core BRICS economies into the global value chains. In contrast, the openness of OASES markets renders them more integrated into regional and global value chains, with the risks of geopolitical disruptions being contained by the fact that all OASES countries are (de jure or de facto) neutral.

The importance of the services sector for employing OASES as a business model platform has a further dimension. According to Michael Porter’s Diamond model, one of the key competitive advantages of nations is the level of development of supporting industries. In this respect, OASES markets offer some of the best conditions in their respective regions in terms of financial services and logistics. The financial sector in the OASES economies is particularly competitive in the segment of wealth management, while transportation plays an important role in the operation of key regional and global connectivity routes.

Overall, the OASES business model offers a range of benefits to companies that are seeking to establish their global presence, particularly in the services sector. These benefits include a diversified network of trade accords expands the scope for product distribution with lower costs; neutrality as a factor that lowers the risks associated with disruptions in supply chains or regulatory disruptions; high levels of economic development and quality of life allow for competition for high-skilled labour and talent. The OASES business strategy may accordingly increase the optionality of the corporate operations across geographies and sectors, while also raising the adaptability of companies to geopolitical and economic shocks.

Yaroslav Lissovolik – Founder of BRICS+ Analytics.

BRICS+ Analytics

English

English