New Players on the Bloc: Is BRICS+ a Critical Challenge?

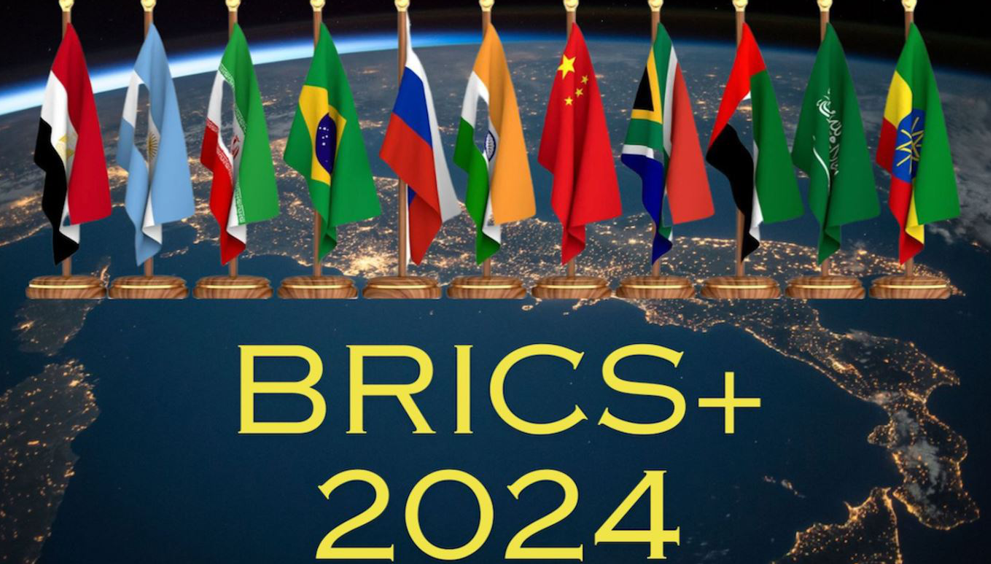

The recent BRICS+ summit in Kazan, Russia, was attended by representatives from 32 countries, with 24 heads of state present. The summit was not only a major diplomatic event for Russia but also underscored a growing push by nations in the Global South to seek alternatives to Western-dominated institutions.

The expansion of BRICS to BRICS+ – starting with the core emerging markets of Brazil, Russia, India and China in 2010, adding South Africa in 2011, and most recently welcoming Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates in January 2024 – introduces new complexities to geopolitics. Indonesia has also flagged participation. This enlarged bloc now encompasses a broader array of resource-rich nations. The expansion strengthens the bloc’s collective power in critical areas such as trade, energy, and payment systems, and could shift geopolitical alliances and partnerships. These developments reflect broader trends towards multipolarity and pose challenges to the traditional rules-based international order.

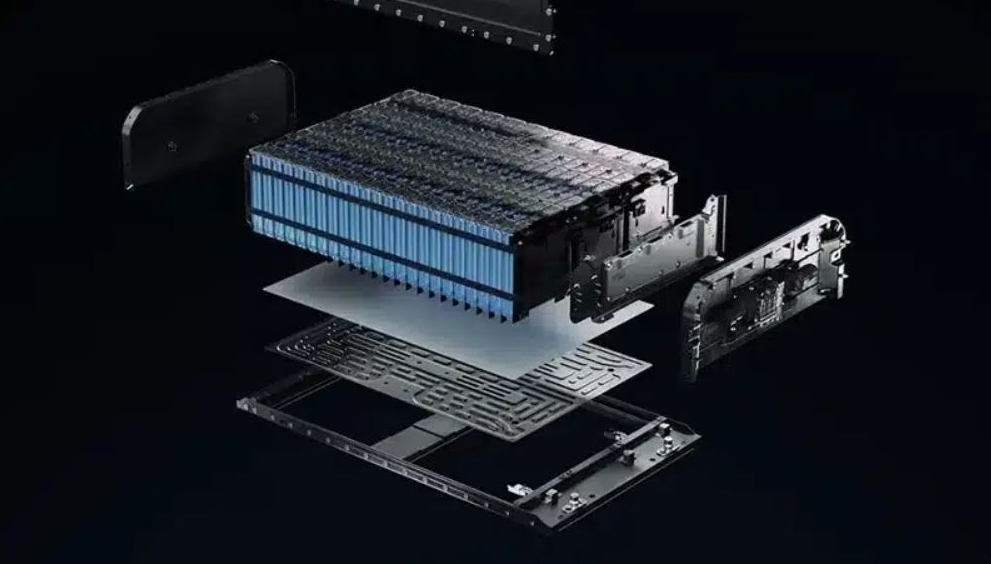

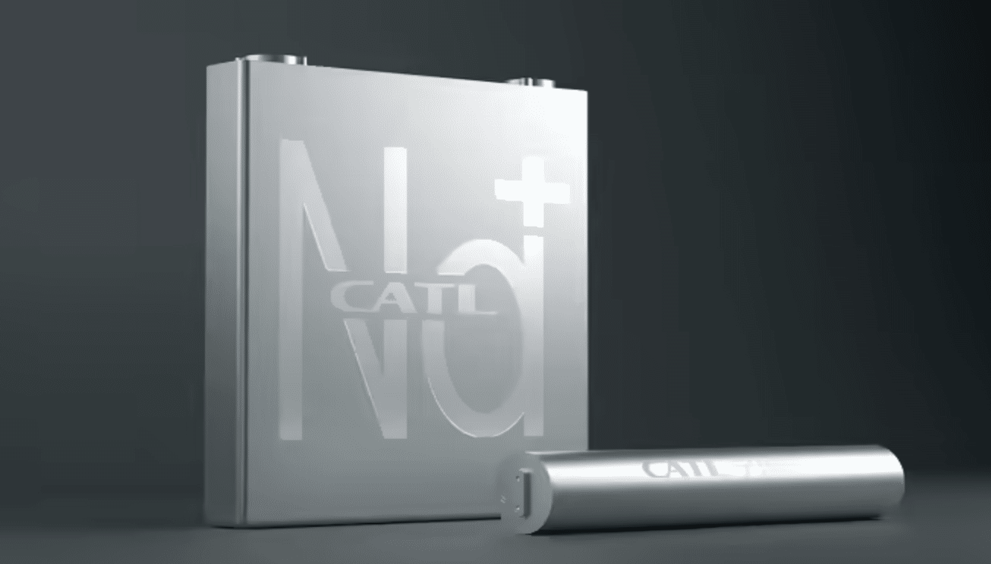

An often overlooked aspect of the rise of BRICS+ is the bloc’s growing collective control over critical resources, particularly critical minerals. This control could significantly effect global supply chains and reshape geopolitical alignments. Critical minerals such as lithium, cobalt and rare earth elements are essential for energy storage, renewable technologies, and advanced manufacturing. As BRICS+ expands its influence, particularly through the inclusion of resource-rich countries such as Iran, Saudi Arabia (whose membership is still pending) and Ethiopia, its control over these critical minerals enhances the bloc’s strategic leverage in industries central to the global energy transition.

This growing influence has the potential to further disrupt existing supply chains for critical minerals. For China, which already controls a substantial portion of these supply chains, the expansion of BRICS presents an opportunity to further consolidate that influence. In recent years, the global policy landscape surrounding critical minerals has shifted dramatically, driven by an “arms race” to secure resources essential for decarbonisation and technological advancement. This shift is, in part, a response to China’s dominance over critical minerals supply chains. To reduce dependence on Chinese processing capabilities, the United States and its allies have launched initiatives such as the Minerals Security Partnership (MSP). These initiatives aim to diversify supply sources, strengthen resilience, and build more robust ecosystems by collaborating with “like-minded” nations.

Australia plays a pivotal role in the MSP. Australia’s Critical Minerals Strategy 2023–2030 seeks to position Australia as a reliable global supplier of key minerals, such as lithium, rare earth elements, and cobalt. Meanwhile, initiatives such as the Future Made in Australia Act aim to shift the country’s focus from exporting raw commodities to producing high-value-added, domestically processed goods. This policy shift reflects a broader global trend towards resource nationalism, as countries seek greater control over their supply chains amid growing geopolitical tensions.

However, BRICS+ complicates this strategy. As BRICS+ grows, it could transform the current China-centric ecosystem into a more bloc-based, self-sufficient system. This expanded network, with a larger resource base, diversified processing capabilities, and potential markets across the Global South, may weaken the effectiveness of the MSP’s efforts to establish a China-independent supply chain.

BRICS+ has the potential to construct a parallel network that bypasses the West, attracting countries seeking alternatives to the Western-led order in trade in critical minerals. This fragmentation of global trade could result in inefficiencies, higher costs, and escalating geopolitical tensions, which may delay progress towards achieving global decarbonisation goals.

The rise of BRICS+ introduces both risks and opportunities for Australia. As a major supplier of critical minerals, Australia has leverage in negotiations with both the United States and China. However, the growing competition between these two great powers and the networks behind them could expose Australia to significant economic and strategic vulnerabilities. Australia is deeply integrated into China’s mineral processing network, with a substantial portion of its critical minerals exported to China for mid- and downstream markets. China’s dominance in mineral processing, coupled with its cost advantages, makes it difficult for Australia to develop alternative technologies and products that can compete with China on a global scale.

At the same time, aligning too closely with the United States through the MSP could limit Australia’s options, reducing its access to China’s extensive processing capabilities and large market demand. This risk is particularly acute if China, through BRICS+, consolidates its access to critical resources through investments and technology transfers, strengthening its hold over alternative supplies of critical minerals. As BRICS+ continues to build a self-sufficient, bloc-based supply chain, Australia may find its strategic flexibility constrained, forcing it to navigate between the bifurcated global supply system for critical minerals.

To mitigate these risks, Australia must adopt a balanced and flexible approach to its minerals diplomacy. This includes engaging with both the United States and China, while diversifying its partnerships beyond these two major powers to ensure strategic autonomy. This way, Australia can secure its position as a critical player in the global energy transition, maintaining its relevance in a rapidly evolving global order. This approach will enable Australia to navigate the challenges posed by competing supply chains while capitalising on emerging opportunities.

By Marina YueZhang

Lowy Institute

English

English