Anti-Western or Non-Western? The Nuanced Geopolitics of BRICS

By Eva Seiwert

The first BRICS+ Summit after the group’s enlargement in January 2024 allowed Russian host Vladimir Putin to style himself as a non-isolated world leader, but the lack of substantial developments on core topics highlights the disparities among its nine member states’ ambitions for the organization, rather than their unity. While BRICS must be taken seriously as a growing economic organization comprising numerous Global South countries, it would be wrong to interpret it as one pole of a two-sided geopolitical competition between China and Russia and the West.

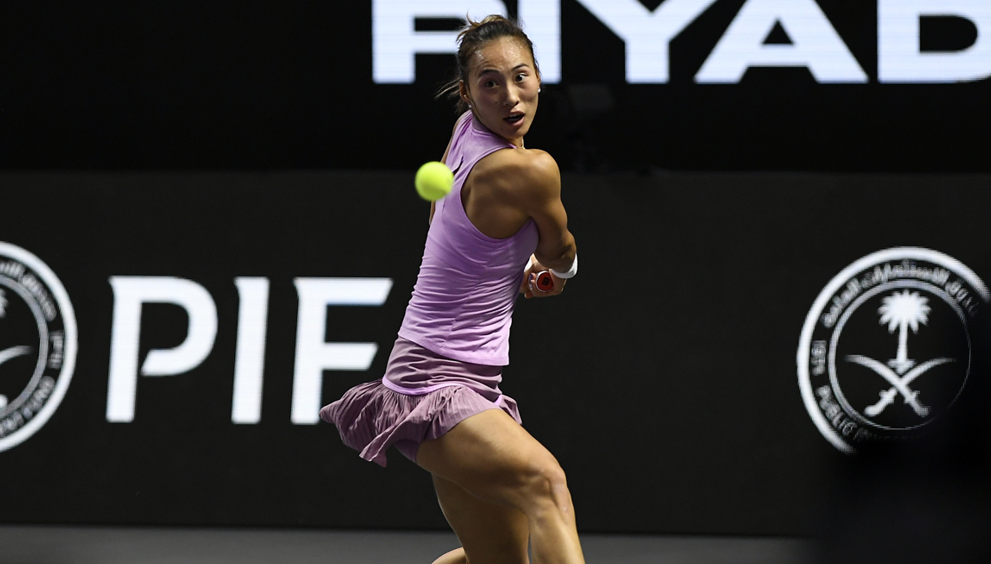

The summit in Kazan which took place from October 22-24 received much international attention, partly due to Putin’s presentation of it as one of the “largest-scale foreign policy events ever” in Russia and the admittedly impressive list of participants. Besides eight of the nine full member states (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Iran, UAE) present (Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took part online due toa recent head injury), over 20 other countries were represented, many of them heads of state. Prominent guests included Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko, and United National Secretary-General António Guterres. As is common at multilateral summits, several leaders also met bilaterally on the sidelines of the summit, with Putin having 17 bilateral meetings on his agenda. Noteworthy was the meeting between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi on Wednesday, which was the first between the two leaders in five years, facilitated by a breakthrough agreement on the Sino-Indian border dispute, one day before the summit began.

Non-western or anti-Western BRICS?

Many Western observers view BRICS as an increasingly anti-Western organization, noting that the summit was held in warmongering Russia, while the group welcomed Iran as a full member in January 2024 and its growth is taking place against the backdrop of China’s geopolitical contest with the US. It is true that the BRICS countries share an explicit ambition of diminishing Western dominance in global governance and strengthening the international influence of Global South countries. Establishing a “more just and democratic world order” has been a core interest emphasized by all members, old and new. BRICS as a group also criticizes Western countries’ use of sanctions and wants to increase the use of local currencies in member states’ financial transactions to decrease their reliance on the dollar.

But reading such measures as an organization-wide proclamation of distinct anti-Western sentiment is a gross oversimplification. While arguably true for some – above all Russia, Iran and to a lesser extent China – other member states do not wish to be seen as part of an anti-Western club. In fact, members such as India, Brazil and the UAE continue to work closely with Western partners – expressed among others in India’s participation in the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue alongside Australia, Japan and the United States. These countries regularly push back on initiatives that are not in line with their own foreign policy agendas. For instance, earlier this month, heavily sanctioned Russia hosted a meeting of BRICS finance ministers at which Russian Finance Minister Anton Siluanov called for creating an alternative to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) as well as a BRICS rating agency, a reinsurance company and a commodities exchange. However, most BRICS finance ministers and central bank chiefs did not even bother attending and sent only junior officials instead.

Summit declaration similarly calls for reforming the Bretton Woods institutions, rather than creating full-blown alternatives. Additionally, the member states agreed “to discuss and study the feasibility of establishment of an independent cross-border settlement and depositary infrastructure, BRICS Clear, an initiative to complement the existing financial market infrastructure, as well as BRICS independent reinsurance capacity, including BRICS (Re)Insurance Company, with participation on a voluntary basis” (emphasis added) – an arguably lukewarm response to Russia’s initiatives. Even when it comes to reducing the primacy of the dollar in international trade – something most member states generally favor – there are many differences on how this can be done, and the expected rise of China’s renminbi as an alternative to the dollar does not sit well with co-member India and others.

Taking members’ interests seriously without overegging the group’s influence

BRICS have indeed seen a rise in applicant states and comprise impressive economic numbers. Its member countries account for 29 percent of the world’s GDP and 40 percent of crude oil production. But there is no need to fear the development of a major geopolitical anti-Western bloc. For this, their interests are far too diverse and include too many countries that value the organization only as a non-Western rather than anti-Western group.

Europe should focus on taking seriously the criticism that binds together all BRICS+ countries, ‘non-Western’ and ‘anti-Western’ alike, which includes Western states’ unfair dominance in core international institutions that no longer reflects contemporary international power realities. But let’s not overinterpret the supposed ‘threat’ of this loose platform. Considering BRICS’ appeal as an alternative to Western-led institutions, there is a clear need for European countries to reassess their strategies for engagement with countries in the Global South. Maintaining and nurturing relationships with individual BRICS countries – like German Chancellor Olaf Scholz is currently doing on his visit to New Delhi for the 7th Germany-India Intergovernmental Consultations – is essential to keeping BRICS+ from ever becoming a truly anti-Western pole.

Eva Seiwert is Analys, Project coordinator.

Mercator Institute for China Studies

Source: merics.org

English

English