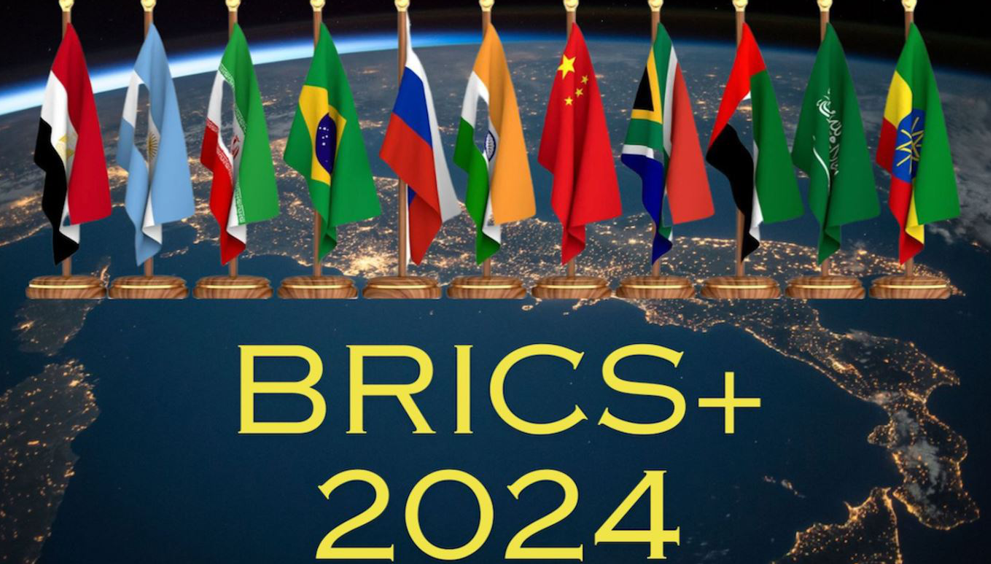

Russia Is Holding Back Other BRICS Members

At a glance, the 16th BRICS summit did not create the anti-Western conclave President Vladimir Putin desired. The final declaration and much of the public discussion were principally dedicated to a raft of financial measures, presented as means to facilitate international trade and development: reform of the United Nations and Bretton Woods institutions, and a two-state solution for the Israel-Palestine conflict were recurrent topics, none of them all that controversial internationally.

In that same vein, Putin peppered his closing press conference with apparent conciliatory gestures, like stating that the summit’s financial initiatives were not meant to be an alternative to established financial instruments. He even took a question – for the first time since 2022 – from BBC correspondent Steve Rosenberg. In a gesture to Brazil and India, Putin also promised no new BRICS members in the near future.

Representatives from 36 countries — including NATO member Turkey — attended, as did UN General Secretary António Guterres. As the Russian BRICS “sherpa” Sergey Ryabkov stressed at the end of the summit, the club is open and not anti-Western in orientation. Hosting the summit at Kazan was meant to communicate that Russia is a land of toleration and coexistence among “civilizations,” another common BRICS theme.

All these elements of the summit might give one the impression that Russia is a respectable member of the international community.

The reality is that today, Russia is dependent on foreign partners to continue its war of aggression against Ukraine. Non-Western trade has replaced all inputs for the Russian economy to stay afloat — however precariously — and keeps providing access to dual-use components. The scale of reported Iranian and North Korean arms deliveries to Russia is staggering, with North Korean shells reaching the millions and Iranian armed drones in the thousands. Recent reports also raise the possibility of North Korean soldiers fighting against Ukrainian forces in Kursk or even in Ukraine.

In this context, Russia hosted the 16th BRICS Summit in Kazan. Unlike Russia’s diminished presence at the 2023 Johannesburg BRICS Summit, this year’s chairmanship gave Putin the opportunity to assert Russia’s status as a major power. Part of this status claim is inherent to the pageantry involved in large summits.

On this point, the Kremlin’s domestic messaging is also important. During the summit, Verstka revealed that Vkontakte bots made over ten thousand comments about BRICS over a few days in one of the Kremlin’s “largest ever” propaganda campaigns.

But messaging, foreign and domestic, is not enough. Russia’s plans need to work to prove it is a major power. At the Kazan summit, Russia’s crucial proposal was the BRICS Cross-Border Payment Initiative along with the development of a payment messaging service. The goal of these would be to substitute SWIFT and evade the use of the dollar – which exposes financial transactions to U.S. jurisdiction – for major financial transactions.

A reduced role of the U.S. dollar and SWIFT are long-standing topics in international trade. But Russia’s renewed push comes at a time of increased global fragmentation and technical acceleration. The Russian proposals would rely on — among other solutions – blockchain applications, for its users to protect themselves against “political pressure, abuse and external sanctions.” BRICS has opposed the use of international sanctions on principle, siding with Russia on the topic since 2014.

Accordingly, documents revealed by Meduza show that Russian propagandists were tasked with presenting the Kazan summit as a success that is making the West nervous”. Yet, as stated by an anonymous BRICS central banker quoted by The Banker, the dollar is set to remain the currency of choice for now, even among members of the organization. Key finance officials from China, India and South Africa did not attend preparatory meetings on the topic before the summit. In the end, Putin had to manage expectations about the proposals. That is why he denied that they were an alternative to SWIFT, a sharp change in rhetoric from it being a step towards the “death of the dollar’s leadership.”

While the spectacle of the summit construed a version of Russia as a major power, the tepid reception of the main policy proposal undermined that effort.

Another element to consider is that BRICS is a club of major powers. To that extent, the comparison with the G7 is relevant, as that group also lacks strong formal rules and remains a rather flexible coalition. This feature reflects a long-standing preference in the Kremlin for international affairs to be led by gatherings of major powers rather than a set of norms. To that extent, the group has remained central to Putin’s evolving vision of a multipolar world, liberated from international law which the Kremlin sees as a Western imposition.

Did other participants share this view? For other BRICS members, the summit functioned as a club. For Egypt and the UAE, the was the venue for a joint outreach effort to Iran. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed — otherwise a pariah due to the Tigray war — held meetings with South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa and spoke at the BRICS Business Forum. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan used BRICS to signal his hedging intentions towards Europe, holding the prospect of membership in the group as a threat. Despite their mutual conflict and rivalry over global South leadership, Chinese Communist Party Chairman Xi Jinping and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi met on the sidelines of the summit. It was the first such encounter since the 2020 clashes when the two countries were on the brink of war. Even Abiy and the President of Egypt Fattah al-Sisi — with whom Ethiopia is locked in an escalating conflict — got to shake hands.

Still, Russia’s war against Ukraine remains a spoiler for the club. Crucially, the war has been construed by the Kremlin as a battle against Western unipolarity. In this twisted narrative, Russia is fighting against NATO in Ukraine in a war that will result in the breaking of U.S. hegemony to the benefit of the global majority.

This notion of multipolarity is far from the more mundane use of the term, and it is thus divisive for the group. Broadly speaking, BRICS is split into countries like Brazil, India and South Africa which view it as akin to non-alignment, and China and Russia which see it as a call to antagonize the West. The group’s 2024 enlargement resulted from the latter gaining the upper hand, especially over those who wanted cohesion over expansion.

Russia should have been suspended from BRICS in 2022 as it was from dozens of other international organisations. Even the BRICS’ New Development Bank stopped working on Russian projects in 2022. Without Putin being part of the club, the division between its members’ intentions might still be there but would be less onerous. Those wishing to build institutions beyond those perceived as dominated by the West could have continued without the implication of helping Russia pursue its war of aggression. There would also be more enthusiasm for the group’s financial initiatives as the threat of sanctions would be avoided.

English

English